For my birthday weekend, I took myself to Bathhouse in Williamsburg. In the steam room, the air was nearly opaque. The wet air took my breath away. I could manage half an inhalation before my chest would seize. UV lights on the ceiling penetrated the steam while condensation dropped on my legs. Gradually my eyes adjusted to the shapes of other people. I couldn't read faces but the general outline of a leg and the monochrome of a bathing suit broke through the steam. When I closed my eyes, I saw streaks of blue like lightning shooting from the bottom of my vision. This sounds more unpleasant than it was. The heat was relentless and my flesh was instantly covered in sweat. The struggle is part of the process, an androgynous voice said as they entered. Yes, I was here to struggle and hopefully feel relaxed by the end. With no sense of time inside the steam room except for the rhythm of people leaving who arrived before me, I listened for a change in the music. I recognized “I'll Come Too” by James Blake and committed to stay until the end of the song.

The staff at the front desk advised I do two hot rooms followed by cold, and repeat, so I went straight from steam to dry sauna. I don’t know if the red light in the dry sauna was the therapeutic kind. I’m not even sure what the therapeutic kind is good for. My breath started to come back and I again wondered about the optimal amount of time to sit and sweat. I draped a towel over my head and quietly narrated the beginning of a story that’s been kicking around my head:

Between 5 and 6 pm a white box truck arrives outside the halal butcher shop on Smith Street. The roll-up door is lifted to reveal a blue tarp curtaining the contents. A butcher walks out of the shop with a canvas bin and wheels it to the back of the truck. A man appears at the back of the truck and drops a goat, gutted and skinned marble white, into the bin. Incredibly pure, and not a color that appears on any flesh dotted with hair or the pattern of veins, the animal is entirely white and red. The color of the goat, or any butchered animal, might best be described as chalk, snow, or gallery wall white. The colorways of a bleached shirt or Santa Claus. The butcher uses a white cloth to veil each additional goat body from view. This happens again and again until the bin, measuring 2’ wide, 3’ long and 4’ high, is full. Then the bin is brought inside. The routine continues with more goats and whole chickens. By the time the truck is unloaded a pool of blood has mixed with motor oil in the gutter and this unholy fluid drips into the sewer.

Feeling like I’d made some narrative progress, I opened my eyes and exited to the pool area.

I don't know how long I stayed in the cold plunge. I entered it by accident: it was the least crowded of the three pools. But after two hot rooms where I'd worked up a sweat sitting still, I welcomed the icy water. I submerged myself up to my neck and saw my breath as I exhaled out across the surface of the pool. I thought about Wim Hof and the protagonist in my friend Francesca’s novel who worships him. Then I thought about the recent New York Magazine profile of Andrew Huberman who produces acolytes interested in optimizing the body’s functions. To be honest, it was less of a profile and more of a dissection of his past affairs and manipulations. Glenn Greenwald, who I've taken to ignoring on Twitter, commented, “I never listened to Andrew Huberman and know little about him, but I kept reading this endlessly gossipy article in this shit magazine, waiting for even a single revelation about his private adult life that merited public interest or knowledge, and never found a single one.” In this instance, I think Glenn is on to something. The article surely means something to the Huberman community and those seeking to expose the manipulative language of self-help machismo. If do as I say, not as I do ever needed a spokesman, it would be Stanford Associate Professor of Neurobiology, Andrew Huberman. A podcaster (last name not Rogan or Cooper) facing this amount of media scrutiny certainly feels prescient of pop culture. I’m left wanting a more specific conclusion, yet perhaps the community formed in the wake of Huberman’s transgressions is a universal lesson on resilience. Also, NY Mag produced some of the best content during the dire media days of COVID (nobody else was reporting on the bucatini shortage), so show some respect, Glenn. When I finally stood up from the 48°F bath, it felt like my skin was vibrating. I wasn't shivering. This was like I could feel the electrical signals coursing through my limbs. Good stuff. This sensation lasted a good ten minutes before I gently stepped into the tropical sauna.

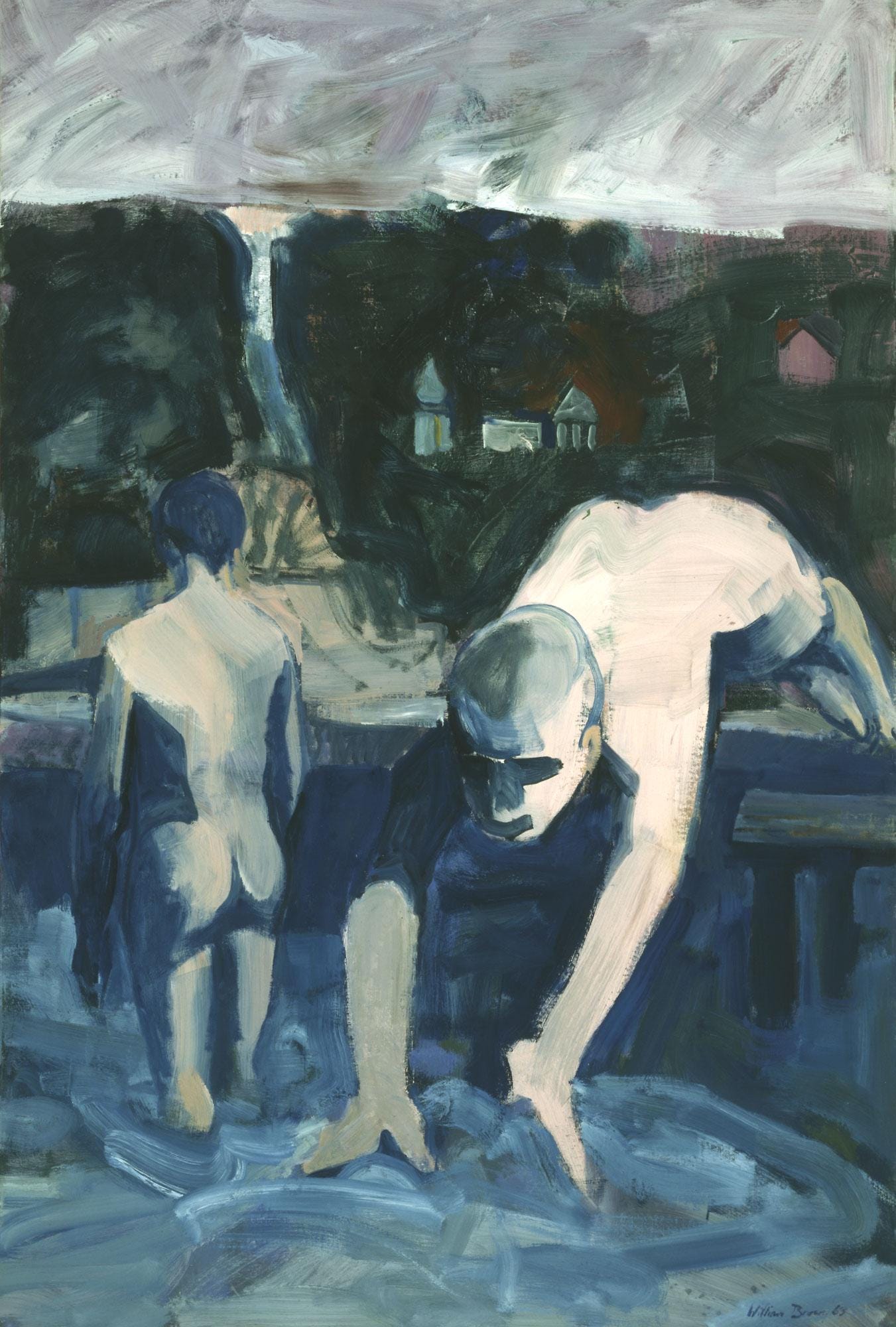

The tropical sauna didn't have music and was also the most comfortable. A perfect humidity that implored me to lie down and close my eyes. My breathing slowed and my muscles achieved the weightless calm that precipitates a nap. I knew this terrible comfort could not be satisfied. Falling asleep in the sauna is definitely how injuries happen. So I sat up straight and mentally measured the bricks that curved in small arches across the ceiling. I thought about looking up the history of this building but, as per Bathhouse rules, my phone was in a locker. There I was in a pair of purple Carhartt trunks, alone with my thoughts at 185°F, thinking about the vulnerability that goes hand in hand with healing. And in that moment of pure relaxation, I thought about Viggo Mortensen in Easter Promises, fighting his way out of the baths. Eastern Promises is spoiled with red and white. It’s not a film about aging, but it is a Christmas film. Red velvet sofas, red dresses, and linen napkins. The red blood spilling from a man’s throat or dripping from a hemorrhaged pregnancy. The white cross-section of a severed frozen finger, or a cigarette filter. The glaring absence of a white winter because, as one Russian mobster complains about London, “It never snows in this city.”

My reflection didn't last long, a class was arriving for the Aufguss ritual. I went to the restaurant upstairs and ate French toast with an Americano.

That night I went to Metrograph to watch La Captive (2000), Chantal Akerman’s adaptation of Proust’s La Prionnière. The opening shot of crashing waves transitions to Sinon watching home movies of young women playing on the shore. One of the women is Ariane, his dissociated lover. The two live in Simon’s grandmother’s apartment, with separate beds and baths. The latter they perform simultaneously, talking to the other through a frosted glass window. Now and then Simon invites Ariane into his room for some juvenile fondling. Simon is plagued by the question, “What goes on between two women that doesn’t between a man and a woman?” Thus, Simon stalks Ariane as she goes to galleries and the opera. He roams Parisian streets, seeing her doppelganger and attempting to model her likeness with a prostitute only to grow impotent when allowed control. Meanwhile, Ariane seems happy to serve as a muse or lover. Ariane is comfortable as Simon’s companion while maintaining implicit lesbian relationships and female friendships. And yet, Simon’s anxiety boils over into a familiar male downfall: pushing the woman away because of pernicious self-doubt forcing her to reiterate that yes, she does love him. Simon, in all his dandyish traits and hypochondriac allergies, is a bit of a buffoon. Ariane’s story ends with a one-way swim into the evening sea. From a different storyteller, this narrative might be sadistic. In Akerman’s hands, it’s an arresting tragicomedy.

Dear reader, I have not read In Search of Lost Time Volume I (shoutout to the homies with that Franklin Library edition on their shelves), let alone Volume V! Allow me to end this newsletter with a moment of cursory research into the details about bathing in La Prisonnière. Late in the novel, the narrator reflects on the death of the author Bergotte and natural versus medical remedies, “We know that cold baths are bad for us, but we like them, so we can always find a doctor to prescribe them for us, if not to stop them from harming us.” I want to believe in remedies, even when I don’t know what I’m curing.